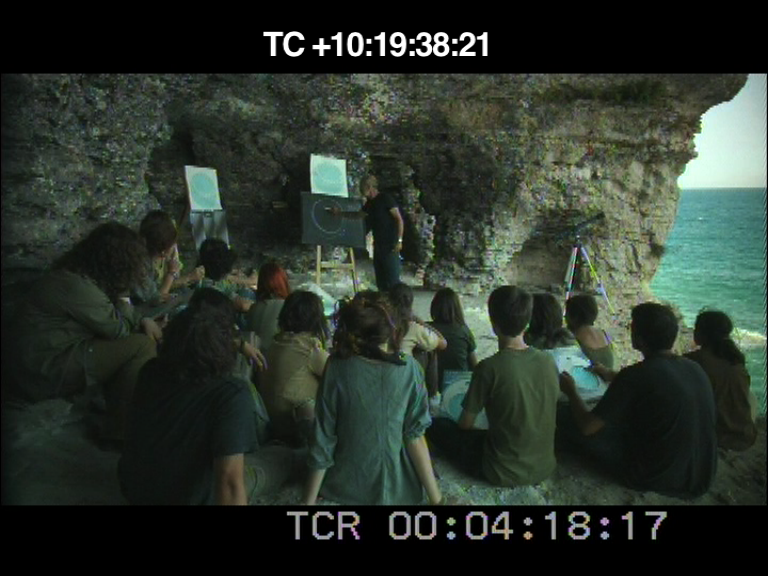

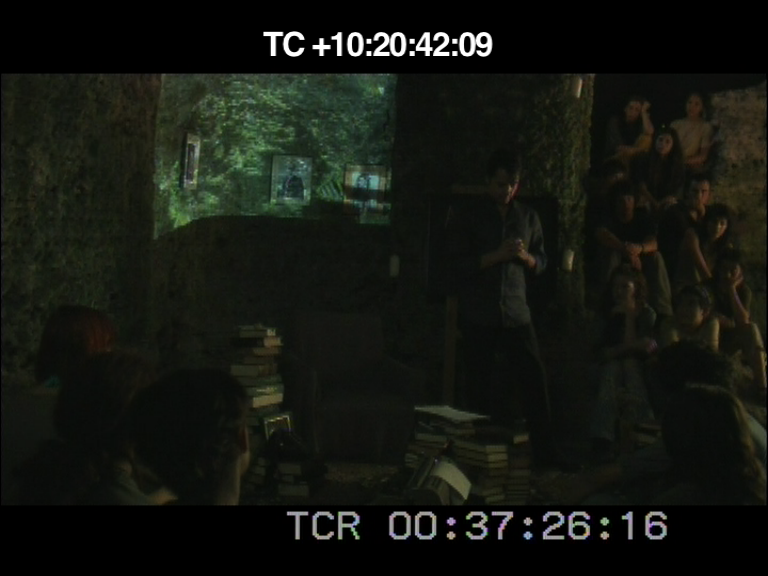

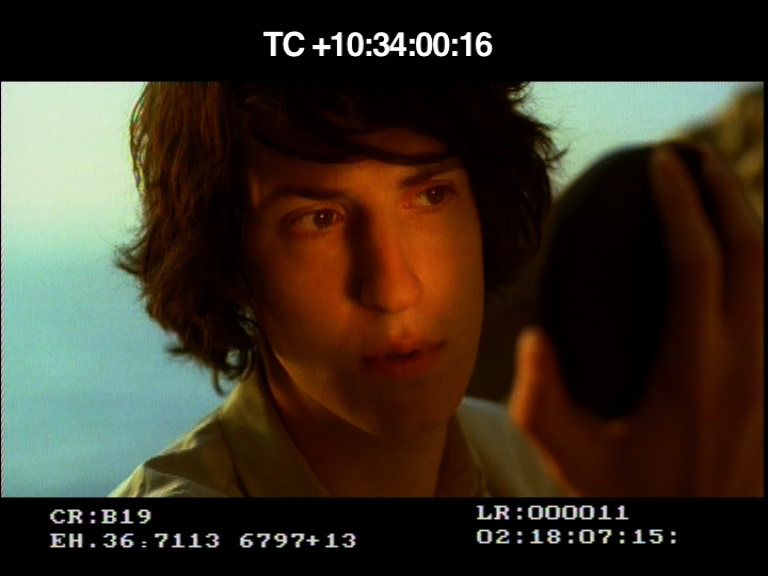

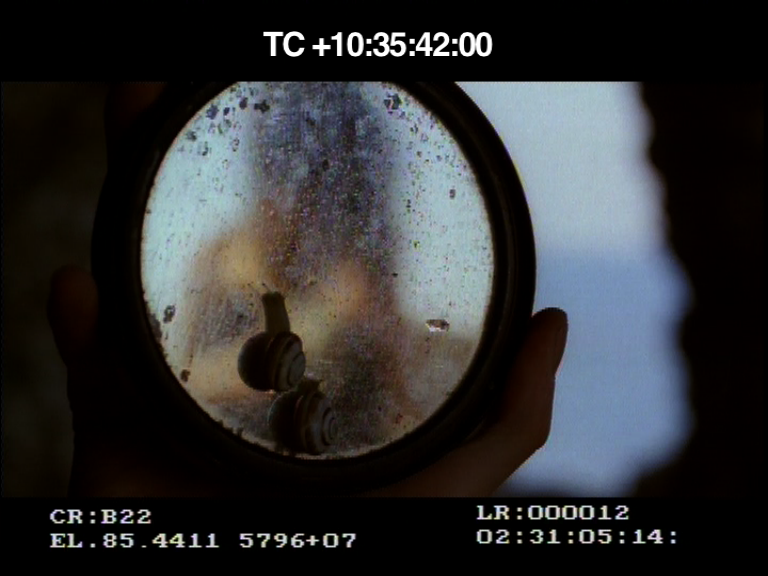

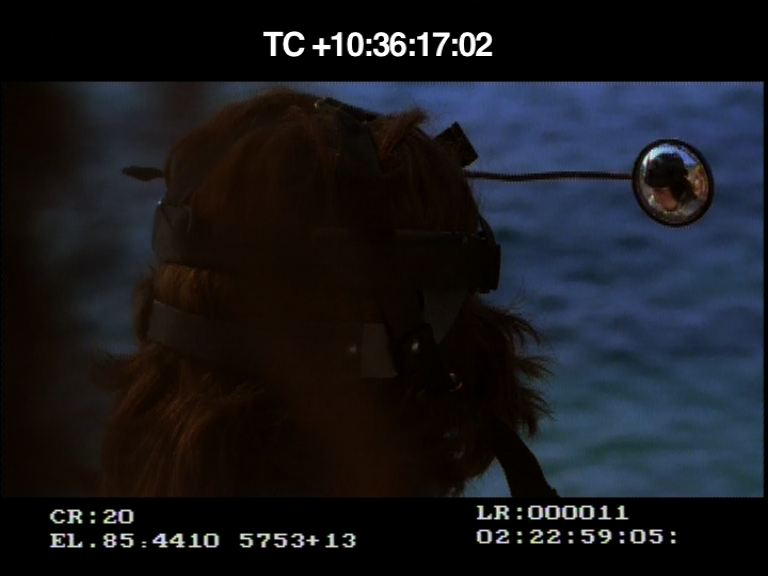

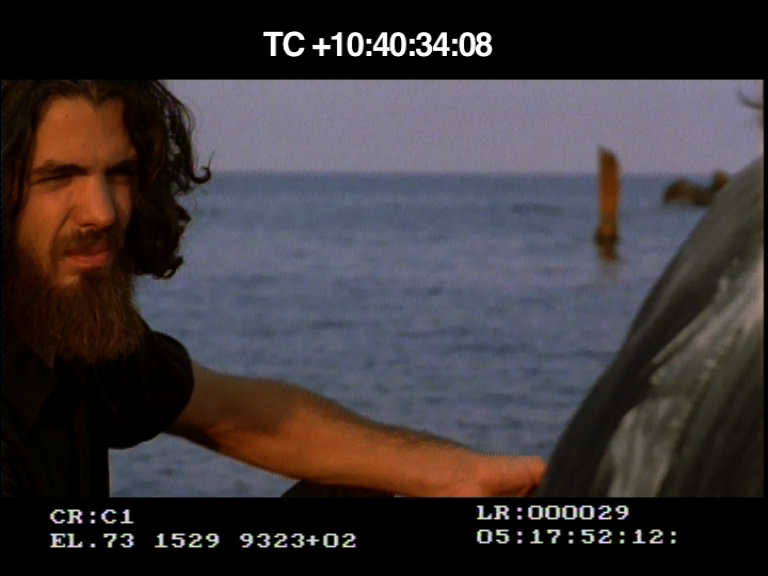

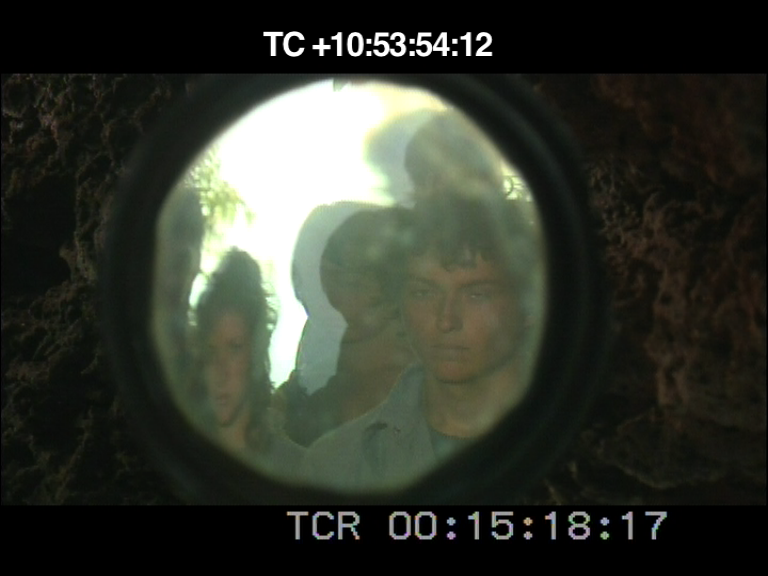

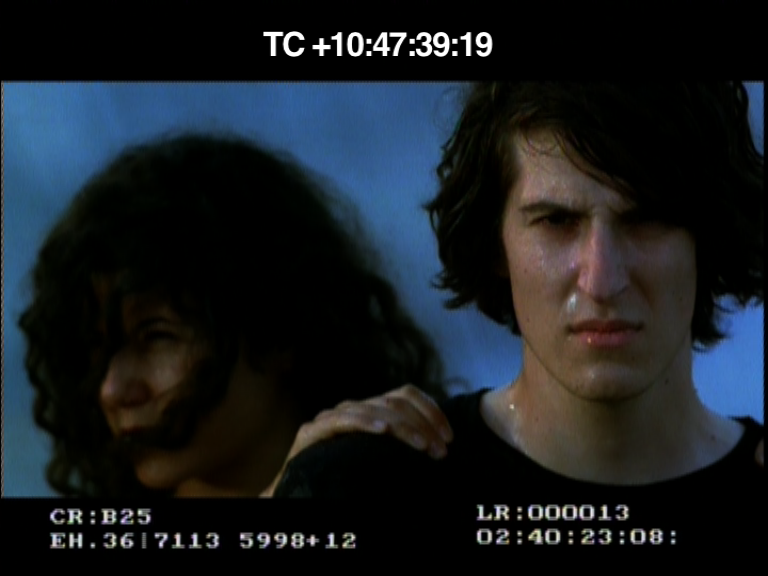

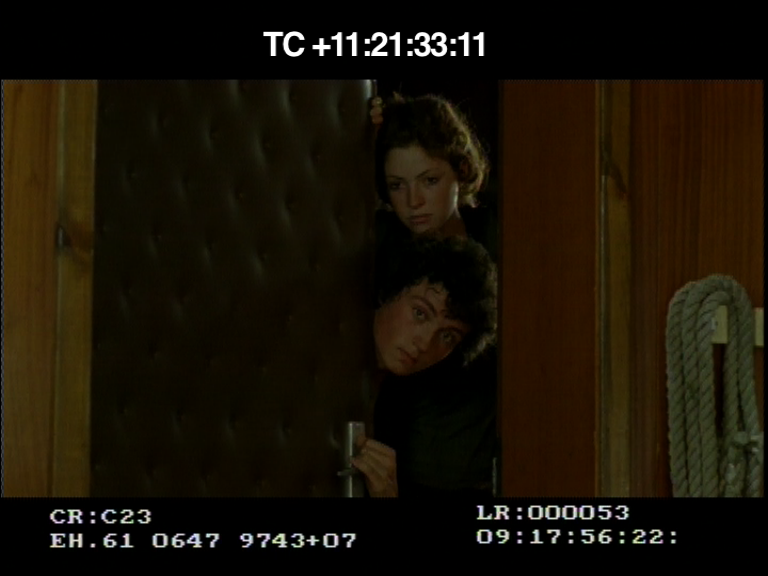

They walk in line. The boy walks first; the girl follows after him. The boy, the present, is trying to look back; the girl, the past, is trying to save herself, but the past is unredeemable and the present is doomed: it falls apart in its very attempt to preserve itself. The present falls apart into quotations, allusions, references, gazes, insecure desire, and useless wisdom. Dissimilated, jumbled, it is no longer this boy, it is a whole community in which the boy is boys, the girl is girls, everyone is anyone, a community of empty people, moved – without action – by shadows.

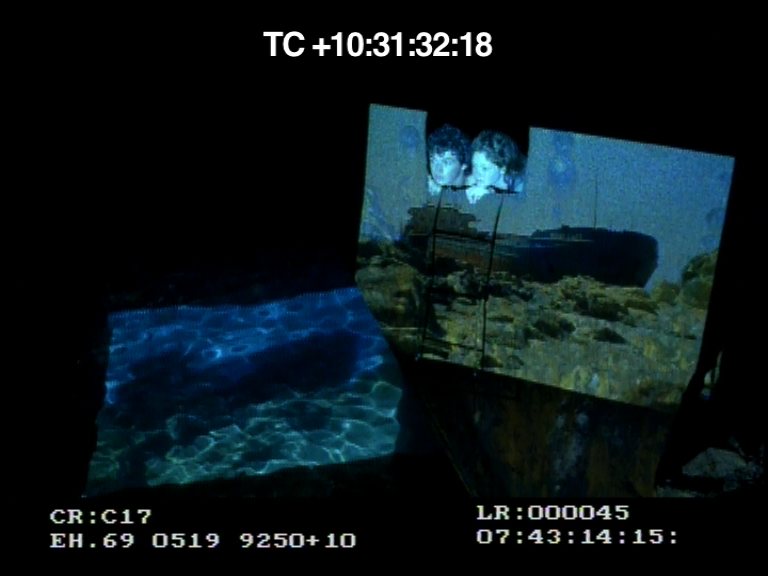

These lines offer a possible approach to Ivan Stanev’s Moon Lake, an approach trying to take into account the amount of knowledge that the film has woven into its paradoxical narrative. This knowledge explains what happens but, being a part of what happens, it cannot be the last instance guaranteeing the meaning of the film, nor a secure standpoint for interpretation, since it offers no super-order, no meta-language. This knowledge opens many doors to the film and yet, it does so not by positioning itself outside (of the work) but, on the contrary, by staying within it, by remaining at the level of the narrative. This is why the lines above, with the explicit reference to Orpheus and Eurydice, offer just one possible approach.

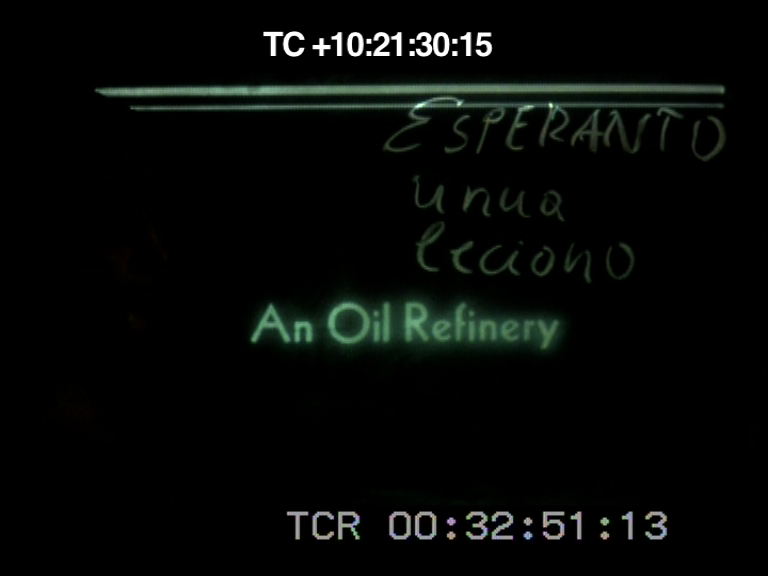

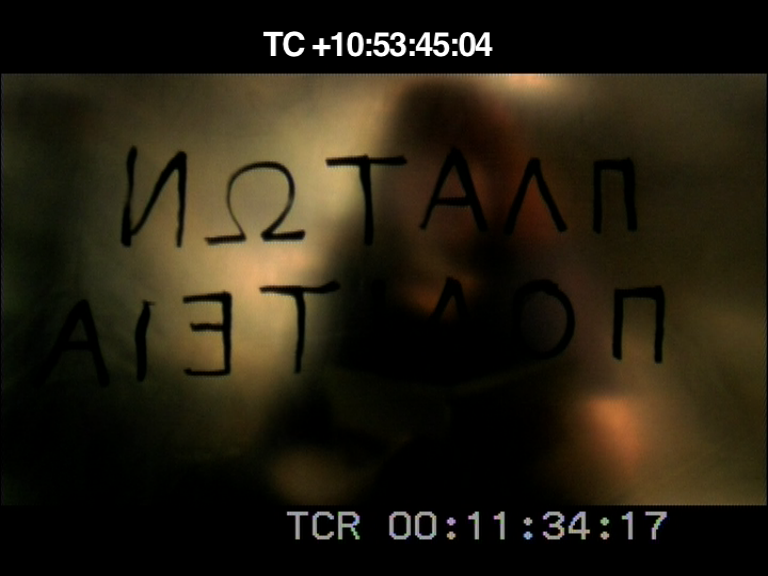

They make no claims that would have been in any way illegitimate: the story of Orpheus who must not turn back if he wants to lead Eurydice out of the netherworld is, in the broadest sense of the term, a quotation among the other quotations in the film from T. S. Eliot, Baudelaire, Rilke, Plato, etc. But, just as this quotation allows us to read all the other quotations and the whole film through it, so can the story of Orpheus and the whole film be read through Rilke, Plato, or Eliot’s The Hollow Men.

Darin Tenev – A VALLEY OF DYING STARS